Pure Fresh Air & Plain Good Food

Why did Bradford need an open air school?

Why build a school for Bradford children in the middle of a wood, right on the outer edge of Bradford? A hundred or so years ago it was practically in the countryside, and there weren’t many children there. And besides, there was already a perfectly good school for Thackley children.

The school that was opened in Buck Wood in 1908 wasn’t for Thackley children, but was intended to help solve a problem that Bradford’s local authority, the City Council, had been trying to deal with for many years. There were still many areas of appalling slum housing in the centre of Bradford. These cramped and badly built homes were close to the woollen mills where Bradford’s factory workers laboured. Many of the children who lived in these poorest slums were unhealthy, because of overcrowding, pollution, and bad sanitation.

Partly because of bad housing, death rates in Bradford were higher than the average for the whole country. There was a widespread problem of chest diseases, particularly tuberculosis, although rates were dropping by the end of the nineteenth century. Another major problem, especially amongst children, was that of infectious diseases, such as epidemic diarrhoea. This was because many slum dwellings still had shared outdoor privies which were impossible to keep clean. When children suffered from poor health and frequent bouts of illness, these living conditions made it difficult for them to recover their health. They missed more and more schooling, and never caught up with their lessons.

Bradford had already begun to tackle the problem of poor health amongst so many of its schoolchildren. The Education Committee had appointed the first School Medical Officer in the country in 1893, to look after the health of the children in its schools. They had also developed the first school feeding programme in country, with centralised school kitchens to prepare and cook dinners for the underfed children of the city.

Why was it build in Buck Wood?

The idea that fresh air could be good for health has a long history. But the practice of educating delicate children in the open air only began at the beginning of the last century. In Germany a school doctor noticed that many ‘backward children’ were in fact suffering from long-term poor health. He strongly recommended open-air treatment for the children, in suitable surroundings, with careful supervision, good feeding and exercise. The first open-air school was opened in pine woods near Berlin in 1904.

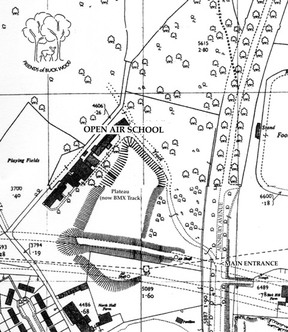

Bradford’s progressive education authority quickly saw that this kind of schooling could well benefit similar children in Bradford. It was one of the very first towns to provide such a service in this country. The Council had recently bought Buck Wood as part of the land belonging to the Esholt Estate, which they needed for developing the sewage works at Esholt. So they used part of the Wood which seemed ideal for the scheme, and the School opened in a temporary building for an experimental term in 1908.

What happened next?

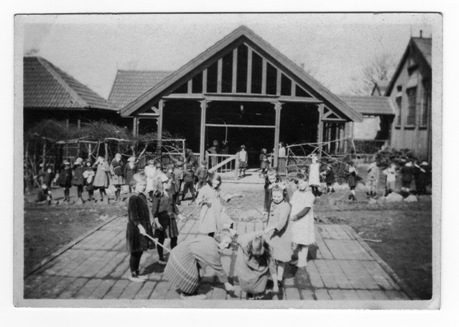

The Open Air School in Buck Wood, Thackley, took in its first trial pupils in the autumn of 1908. Forty ‘delicate’ children were brought by tram from the city centre each weekday for lessons and meals at the school. The pupils spent as much time as possible in the open-fronted south-facing classrooms and in the woodland itself. By the end of the term it was clear that the children were much healthier and most were well enough to go back to normal school.

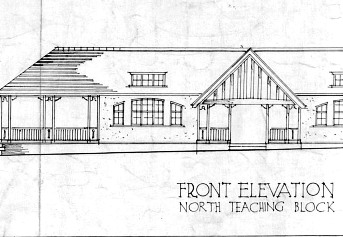

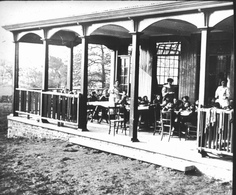

It was decided that the school should continue, and the new buildings were designed. They were very different from the school buildings that children were used to in the past. Schools were built to be functional, not comfortable. They had lofty classrooms with windows placed too high for the children to gaze out of. Walls were painted in practical dark colours. The only heating was from hot-water pipes or open fires, and the buildings were so cold in the winter that both staff and children had high rates of absence because of chest, nose and throat infections. But the Open Air School was designed on very different lines, with lots of light and fresh air circulating – although it too could be very cold in winter!

It was built facing the grassy slopes of the raised area formed from waste material excavated from Thackley railway tunnel. This is now the Plateau, where there is the BMX cycle track. The children could play up there as well as in five acres of woodland, which included a field, allocated to the School.

In the first temporary building there were just two classrooms, kitchens, etc., and a dining room with an open veranda. Very soon a row of other chalet-style buildings were added, making space for 120 children. They were arranged in a long line, stretching out from the original central block. Each of these wings – one for boys and one for girls – contained not only classrooms with open verandas, but also resting sheds where the children slept every afternoon. Behind was a long corridor connecting the kitchens, toilets, baths and showers, storerooms and offices for the staff.

By the time the school closed in 1939, thousands of Bradford’s sickly children had benefited from the special care and atmosphere offered by the school.

How were the children chosen for the school?

At first the children who came to the School were from Bradford’s poorest slums. They included children with diseases such as tuberculosis, rickets, anaemia, and chronic infections. The first group of children were described by the School Medical Officer (SMO) as being ‘debilitated and below par, consequent upon the presence of some pathological condition, such as tuberculosis…’

All needed a few months of fresh air, good food, and exercise to build them up. In later years the children came from better homes, but were still struggling to recuperate from childhood illnesses such as scarlet fever, diphtheria, and from tuberculosis which was still a problem in Bradford. There were also more children with chronic conditions such as asthma and anaemia. They were no longer solely those illnesses associated with poverty or neglect.

Children were usually selected for the School by the Bradford SMOs. They could be referred to the SMO by their teachers, School Nurses, or other doctors. Their health was carefully monitored whilst at the School, by the Medical Officer and by School Nurses. They were regularly weighed and measured and had their blood tested. The children were given supplements such as ‘Parrish’s Chemical Food’, Virol, and cod–liver-oil-and-malt. Hot and cold showers and baths ensured that they were clean, and that skin problems were dealt with promptly.

The pupils attended for up to a term and generally that was enough for a marked improvement in their health, although some returned later.

What was the school day like?

The pupils arrived by tram at Thackley Corner, and walked in a crocodile down to Ainsbury Avenue and Buck Wood. Their day was long, but was not all hard work.

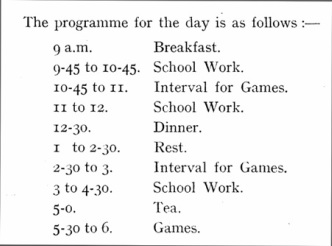

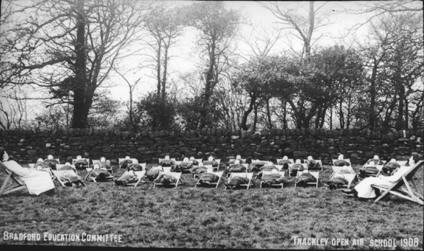

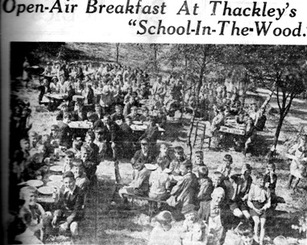

The day began with breakfast at 9 a.m, and ended with games from 5.30 to 6 p.m. after which they were bussed back to the city centre. In between were lesson periods, games, meals, and the compulsory rest period in the afternoon. In the open resting sheds, which had rolling shutters for wet and windy weather, or out in the Wood, the children were wrapped in blankets and had to lie perfectly still on camp beds for an hour and a half. This was seen as a vital part of their health care.

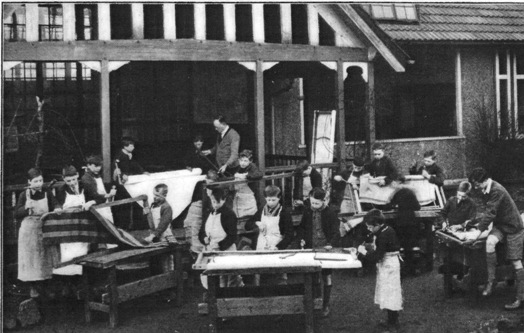

As far as possible school work and lessons were done in the fresh air, often in the wood itself or the playing field at the back of the school. As well as normal lessons the girls were taught domestic skills which they put to practical use in the school kitchen and dining room. The boys were taught useful crafts such as woodwork, and gardening. All had nature study lessons and walks in the surrounding woodland.

The gardening lessons soon became an essential part of the school day for both boys and girls. Apart from providing exercise, the garden plots could be used in maths, writing, and drawing lessons, and the fruit and vegetables contributed to the school meals.

What did the pupils eat at school?

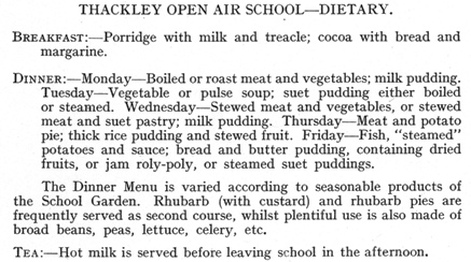

The meals were an important part of improving the children’s health, and the staff made sure that all the food was eaten up. But the porridge and treacle the children were given for breakfast was a dish so much disliked that many pupils remembered it several decades later, and some never ate porridge ever again.

Dinner was a generous 2-course meal, with solid desserts such as jam roly-poly or steamed suet puddings. Rhubarb was grown in the gardens and used regularly for desserts. The last meal was tea, which included milk, bread and butter, or fruit cake. On such a substantial diet, the average weight gain of a child attending the Open Air School for a term was over 2½ kilos.

Why did the children have to sleep in the afternoons?

Many older people can remember having to lie down and rest in the afternoons when they first started going to school, but at the Open Air School there were special open sided ‘Resting Sheds’ where everyone had to lie down on camp beds for at least an hour and a half in the afternoon.

Before they did so, the children had to clean their teeth. They were provided with their own toothbrushes and towels, and had to learn how to use them properly. At the same daily session they were also taught ‘handkerchief drill’. This was to make sure that they could breathe through their noses and not their mouths, which was thought to be a bad habit, as well as being unhygienic.

It was peaceful in the Wood, and the quiet period of rest or sleep was thought to be essential to the children’s return to good health. The children were wrapped in blankets and had to lie still. If the weather was good they could sleep outdoors in the playing field at the back of the School. The teachers watched them to make sure they kept still and had a good rest.But if the weather was bad they were not well-sheltered even in the resting sheds. Their blankets got wet sometimes, and the classrooms would be festooned with damp woollen blankets.

How big was the school?

The Open Air School grew until between 200 and 300 pupils of all ages at a time were taught there.

For a short while there was residential accommodation for a small number of boys who were thought to need extra attention. They were looked after by teachers, and slept on the camp beds at night in the existing buildings. There were also plans to extend the School into the field behind, and another time to build a much bigger residential school in a nearby part of the Wood. But these never took place because the money wasn’t available when Bradford, like other places, was hit by the depression of the 1930s.

There was always a great need for this type of schooling in Bradford, and there were usually waiting lists for places at the Thackley school. When demand was highest the length of time many children spent at the school had to be shortened to less than a full term. Another open air school started in Odsal in 1927, and more special needs schools were provided in Bradford during the first half of the twentieth century. In the 1930s a sanatorium school for children with tuberculosis from Bradford was opened in Grassington in the Dales.

How long was the school open?

In June 1939 there was an article in the Bradford Telegraph & Argus painting a picture of the delightful conditions provided in Buck Wood for the Open Air School pupils. It described them having ‘a hearty breakfast in the sunshine and open air, with trees around them and birds fluttering down to their tables’.

But this idyll was soon to end. War broke out in September that year, and Bradford’s schools were transformed by the plans that had been made to safeguard pupils, staff and buildings.

Thackley Open Air School closed on the outbreak of World War II, its pupils were allocated to other schools, and it was never again used as a special school. During the war the buildings were used by the army at times, by the Home Guard, and various other organisations. The raised plateau became a site for an anti-aircraft gun, because of the area’s proximity to the Avro aircraft factory at Yeadon, and an air-raid shelter was built underneath.

After the War there were hopes that the School would reopen as an open air school again, but this never came to fruition. For over a decade from the late 1940s onwards the buildings were used as a temporary accommodation for children whose new school buildings elsewhere in Bradford weren’t ready in time. Thereafter it was a popular place for community groups such as Scouts and Guides to meet, and other organisations held events there. The school was the basis for summer holiday camps for local children whose parents worked in Bradford factories. Local school classes continued gardening there, and used the playing field for sports, but the buildings gradually fell into disrepair.

The school and the Friends of Buck Wood

The buildings finally burnt down in 1966, and most of the site was cleared for safety reasons. It was abandoned to nature, and was rapidly disappearing altogether, along with peoples’ memories of it, until the Friends of Buck Wood decided to clear some of the site, and to publicise the school’s history.

We have researched the history of the school, and with the help of reminiscences from former pupils, celebrated the centenary of the opening of the School with the publication of a book, ‘The School in the Wood’.

Copies of the 54 page illustrated book are still available from the Friends, priced £3. Our details are available on the ‘Contact Us’ page of this website.

A working group from the Friends regularly clears as much regrowth as possible from some of the building bases, the path following the line of the front of the school, and from the steps leading down to the school from the Plateau.